Page Content

Effects on Conditions of Professional Practice

“We shape our tools and they, in turn, shape us.”

—Marshall McLuhan

Introduction

In 2011, the Alberta Teachers’ Association and a research team from the University of Alberta collaborated on a study of teachers’ experiences with flexible and/or digitally mediated learning environments. The study obtained data on teachers’ efforts to make student learning more flexible using emerging technologies.

The study found various ways in which flexible timing and pacing of instruction affects teachers and their workload. Data was gleaned from more than 1,450 K–12 educators about their conditions of professional practice. At present, the study is the largest of its kind on this topic in Alberta and of any population of teachers in Canada.

The following article highlights the study’s major findings; the detailed research study is available online from the Alberta Teachers’ Association website (www.teachers.ab.ca). Under Publications, click on Research Updates and then click on Impact of Digital Technologies on Teachers Working in Flexible Learning Environments.

In general, survey respondents were experienced teachers who engage regularly with digital technologies. For the purposes of the study, flexible and/or digitally mediated learning environments were classified into three categories:

1. Face-to-face teaching environments in which digital technologies are used as a component of students’ learning experiences.

2. Primarily digitally mediated learning environments, such as online learning, e-learning and/or distributed learning.

3. Outreach schools and/or distance education.

Background

Digitally mediated learning environments enable teachers to personalize instruction and make it more flexible with respect to timing and pacing instruction. Some research on distributed learning suggests that personalized learning environments are conducive to student performance, resulting in achievement results that are comparable to traditional delivery methods (Greenberg 2004; Cavanaugh 2001). Although digitally mediated learning environments bring about flexibility and may support personalized learning (McRae 2011), they also commensurately affect teacher workload (McRae et al 2009; Spector 2005; Thompson 2004; Bonk 2002; Schifter 2002; Kearsley and Blomeyer 2001 and Fuller et al 2000). The literature suggests further that the factors responsible for an enhanced workload are individualized communication and personalization (Cavanaugh 2005; Sellani and Harrington 2002; Tomei 2004).

Technologies once used almost exclusively in digitally mediated environments are increasingly deployed in traditional face-to-face teaching environments. Murphy and Rodriguez-Manzanares (2009) observed that content-management systems, online reporting tools, e-mail and other technologies are used to individualize communications between parents, students and teachers. However, as noted in this study, individualized communication with parents may in fact “depersonalize” the reporting of student progress as parents begin to look only to a quantitative representation of their child’s learning via the online reporting tool. It is increasingly important for Alberta teachers to understand how emerging technologies are affecting their overall workload and conditions of professional practice.

Major Findings

Teacher Satisfaction

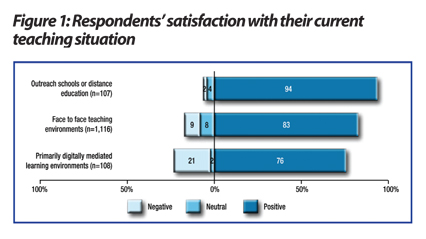

1. More than 80 per cent of respondents rated the experience of teaching in their current “flexible” setting as positive, yet only 63 per cent indicated they would recommend such a situation to others. With reference to their overall experience, outreach teachers, at 94 per cent, were the most positive group and those in a primarily digitally mediated learning environment were the most negative (20 per cent rated their fully online teaching experiences as negative). Participants’ satisfaction with their teaching experience and the likelihood that they would recommend their work to other teachers was independent of years of experience (See Figure 1).

Focus group discussions revealed three possible explanations for the 20 per cent difference between satisfaction scores and participants’ willingness to recommend their particular teaching situation to others.

- Deterioration: Teachers were satisfied with their current situation but would not recommend the teaching profession in general because they felt working conditions were deteriorating with respect to workload, role expansion, and lack of personal and professional boundaries.

- Attainment: Teachers reported a level of comfort and satisfaction with their situation but felt that substantial effort was required to attain mastery and satisfaction. These individuals would be less likely to recommend their situation because of the learning curve and the commensurate stress associated with initially taking on the role.

- Uniqueness: Teachers felt their current situation was well suited to them but that it would not be suitable for incoming teachers who might not share their specific interests and aptitudes.

Expanding Roles for Teachers

2. Many focus group participants expressed concern about the ways in which they were assigned tasks outside their primary role as teachers. For example, participants reported that due to budget cuts, they had to shoulder additional duties, such as providing technical support or counselling students with complex social and emotional needs. Additional duties varied depending on the type of flex environment in which the teacher was working. (A discussion and analysis of the expanded role of teachers appears on page 22 of the full research report.)

Online Reporting and Learning Analytics

3. Participants observed that online reporting platforms and learning analytic tools, because they enable information to be shared immediately with parents, are dissolving the boundaries between work and personal time. Some parents, for example, expect assessments to be posted a few hours after a student has turned in an assignment. Others expect teachers to respond before the start of the next work day to e-mails that were sent after school hours. In short, systems that afford “anytime access” are creating the expectation of “anytime service.” Participants observed that in the absence of overarching guidelines to manage expectations around parent–teacher interactions, individual teachers were left to establish and maintain their own boundaries.

Focus groups stated that online reporting platforms are often unreliable and in some circumstances diminish the opportunities for teachers to engage in meaningful conversations with parents about student progress. A particular concern is when parents look only at the quantitative representation of their child’s learning through the online reporting tool, as it may in fact depersonalize a dialogue and interactions between teacher and parent.

Lack of Time

4. The study suggests that lack of time is the most significant factor restricting a teacher’s ability to provide instruction. Duties such as reporting student progress online, developing individualized program plans, organizing extracurricular activities and communicating electronically with parents frequently all reduce the amount of time teachers have to prepare for classes. Compared with face-to-face and outreach teachers, teachers in primarily digitally mediated environments, not surprisingly, spend a smaller proportion of their time directly instructing students and a correspondingly greater portion of their time on tasks such as marking and contacting parents. Large classes, online and offline, significantly restrict the amount of time and level of assistance that teachers can provide to individual students.

Technologies: Frequency of Use and Pedagogical Usefulness

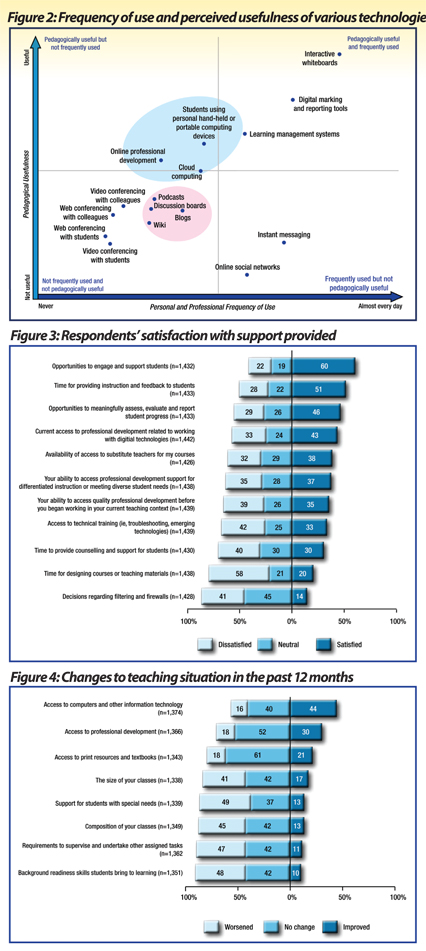

5. Teachers and administrators were overwhelmingly positive about the potential of technology to render the timing and pacing of instruction more flexible. Teachers working in a primarily digitally mediated learning environment are more frequently engaged than their face-to-face and outreach colleagues in online activities such as instant messaging, Web 2.0 tools, video conferences and Web conferences. They also find these activities more useful in meeting their teaching requirements. Outreach teachers make the most frequent use of digital marking and reporting tools (68 per cent use them almost every day); whereas face-to-face teachers make the most frequent use of interactive whiteboards (53 per cent of them use them almost every day). On the cusp of frequency of use and perceived usefulness are students’ personal hand-held or computing devices, cloud computing and online professional development—three areas worth careful consideration in the near future (See Figure 2).

Participants rated interactive whiteboards and administrative technologies (for example, learning management systems) the highest in terms of frequency of use and usefulness. It’s worth noting these are mandated technologies in many school jurisdictions. Conversely, social networking technologies (for example, instant messaging and online social networks), although used frequently, were perceived to have little usefulness for teaching and learning. Participants raised two specific concerns about social networks:

- they may increase the prospect that teachers inadvertently overstep the professional boundaries between themselves and their students; and

- students may object to allowing teachers to access their social networks for pedagogical purposes. Participants deemed video conferencing to have little value in increasing the flexibility of instruction. Indeed, 83 per cent of respondents reported that they do not hold video conferences with students, and only 20 per cent of respondents felt that video conferencing was useful in making instruction more flexible.

Filtering and Firewalls

6. Lack of technology and restricted access to technology due to filters and firewalls were cited by participants as factors limiting their ability to make teaching and learning more flexible. Participants noted, for example, that technology is not always available for every student; teachers often don’t receive the PD they need to use technology in a way that fully supports learning; and many available technologies are unreliable (See Figure 3).

Factors Enhancing and Restricting Instruction

7. Respondents reported generally low levels of satisfaction with the support they receive in their teaching situations (see Figure 3). They were most satisfied with support that is directly related to their interactions with students. Except for technical support, teachers working in outreach schools/distance education are more satisfied with the support they receive than their face-to-face and primarily digitally mediated colleagues. Participants were least satisfied with the availability of support related to developing and planning instruction. Such support includes time to design courses and access to PD related to the use of technologies.

Changing Conditions of Professional Practice

8. Overall, participants reported that, compared with the previous year, their conditions of professional practice had worsened or stayed the same rather than improved (see Figure 4). Teachers were most negative in their assessments of items related to class size and composition. Many participants reported that the readiness of students to learn (for example, ready, willing and able) had significantly declined in the last year. How focus group participants defined student readiness depended on the specifics of their teaching situation. In general, however, participants focused on two aspects of readiness:

- Physical and emotional readiness: Students who are not physically and emotionally ready to learn are less likely to achieve their learning goals. Their lack of readiness may be the result of such factors as hunger, sleep deprivation, anxiety or emotional distress. What participants had to say about physical and emotional readiness varied greatly within and across focus groups and was directly related to the participant’s particular teaching situation.

- Academic readiness: To progress in school, students need to have strong foundational skills upon which to build new knowledge. Teachers assess a student’s academic readiness in order to determine the appropriate level and pace of instruction. Several participants in the focus groups observed that students’ academic readiness is declining. Participants also noted that students vary in their digital readiness and that, as a result, educators should not assume that all students have the requisite digital skills to succeed in a flexible learning environment.

Summary

The study is relevant not only because the concept of “flexible learning” is increasingly dominating system-level discussions about the transformation of education systems (Alberta Education 2010), but also because the exponential growth in digital technologies is profoundly affecting our personal and professional lives and the ways in which we interact as a society. The study’s findings acknowledge that technology integration presents the education system, and its many players, with significant opportunities and challenges.

The research findings underscore the teaching profession’s need to explore and discuss the interrelationship between curriculum, pedagogy and technology. In particular, findings suggest the need to examine how the current industrial model of schooling can be modified to enhance the highly relational space of learning and take into account today’s complex societal needs. It also highlights the potential issues that “at any time, at any place and at any pace” teaching could have on workload with expectations of “anytime service.”

In some cases, policies concerning digital technologies for learning have been hastily developed in the absence of research-based evidence, thereby not accounting for the Alberta situation about the impact of these technologies on teaching and learning. A thorough exploration of the influence of flexible and digitally mediated learning environments on the work life of teachers is needed.

Overall, study participants rated their current experience working in flexible teaching environments as positive. Outreach teachers were the most positive, whereas those working in a primarily digitally mediated learning environment were the most negative. Although respondents had many good things to say about their teaching situation, they also raised significant concerns about their workload. Among the factors that respondents cited as contributing to their increased workload were larger and more diverse classes, supervision and the expansion of their role as pedagogical leaders.

Many participants observed that reductions in staff had contributed to increased workload. For example, teachers have had to provide technical support or provide counselling to students with complex social and emotional needs. These additional responsibilities diminish the ability of teachers to create engaging and effective learning environments and build strong pedagogic relationships with their students.

The study suggests that competing demands on time are the most significant factor restricting a teacher’s ability to provide instruction. Such duties as reporting student progress online, developing individualized program plans, organizing extracurricular activities and communicating frequently with parents all reduce the amount of time that teachers have for interacting with and teaching students. Many participants noted that online reporting tools, because they enable information to be shared immediately with parents, dissolve the boundaries between work and personal time. In essence, more flexible systems that afford “anytime access” create the expectation that teachers will provide “anytime service.” In the absence of overarching guidelines to manage expectations around parent–teacher interactions, teachers are left to establish and maintain their own boundaries. In some cases these same online reporting tools are also seen as creating a distance between parents and teachers where a quantitative number is used to communicate student progress over a deeper and more meaningful conversation with the teacher.

Interestingly, the study reveals that teacher–student ratios differ considerably across the three teaching environments (face-to-face, digitally mediated or outreach/distance learning). The ratio of students to teachers is particularly high in primarily digitally mediated environments. This situation, coupled with the fact that some teachers in digitally mediated environments are on temporary contracts, caused some respondents to remark that they felt like “paid markers.” The digitally mediated respondents noted that the fully online learning space is increasingly being misperceived as a “dumping ground” for students who are unable to succeed in group-paced courses. Some participants suggested that students should be evaluated to determine whether they have the knowledge, skills and attributes necessary to succeed in nontraditional or more flexible teaching and learning environments.

Respondents teaching in digitally mediated environments also believe that they should have the same level of flexibility with respect to scheduling their work as do their students. Many respondents reported that they were asked to support self-paced students within the confines of the traditional workday. As a result, teachers were not often available when their students needed them. Respondents also pointed out that the funding models, work schedules and role definitions that apply to traditional face-to-face environments cannot be applied wholesale to nontraditional teaching situations.

In terms of the potential of technology to make the timing and pacing of instruction more flexible, both teachers and administrators were overwhelmingly positive. They often remarked that technology helped them to personalize and improve instruction and make it more flexible in terms of timing and pacing. The study also reveals that some jurisdictions have taken what was termed a “ready-fire-aim” approach to technology: implementing new technologies before teachers have had an opportunity to learn how they work. The research underscores the importance of ensuring that new technologies are introduced more thoughtfully so that they can be properly tested and so teachers receive adequate training in the use of technology to enhance learning. The pre- and post-implementation supports for teachers and administrators are crucial to the change process.

The findings of this study also raise questions about the financial expenditures and human resources that have been allocated in Alberta toward video conferencing as a provincial strategy intended to make instruction and access to learning more flexible for all students. This study clearly indicates that the vast majority of teachers (83 per cent) seldom use video conferencing, a technology that only one-fifth of the study participants find pedagogically useful. Therefore, video conferencing investments should be prioritized for areas of specific and defined need, for example, rural schools that do not have easy access to professional development or specific pedagogical expertise.

Given a scarcity of financial, technical and human resources across Alberta’s public education system, a more thoughtful consideration of investing in technologies would be prudent to allocate these learning resources in areas where there is a defined and pedagogically appropriate need. When allocating funding for technology and professional development in the near future, Alberta would be well advised to take into account what this study reveals about the perceived pedagogical usefulness of various technologies and the frequency with which they are actually engaged (see Figure 2). Along with this are considerations regarding to what extent teachers are efficaciously involved in the decisions around which technologies are chosen by their school jurisdiction to enhance student learning (for example, online reporting tools and/or interactive whiteboards).

The authors hope that this research study will stimulate a vigorous debate about the true nature of learning in a digital era and the role that technologies can play in transforming the teaching and learning process so that it optimizes student learning in a balanced and humanistic way. In addition to having ongoing conversations about what constitutes effective flexible learning environments for students and the appropriate conditions of professional practice for teachers, Albertans also need to begin talking deeply about the kind of society they want to create in a digital age.

References

Alberta Education. 2010. Inspiring Action on Education. Edmonton, AB: Alberta Education. Available from http://engage.education.alberta.ca/uploads/ 1006/20100621inspiringact86934.pdf (accessed October 15, 2010).

Bonk, C. 2002. “Online Teaching in an Online World.” USDLA Journal 16, no. 1.

Cavanaugh, C.S. 2001. The Effectiveness of Interactive Distance Education Technologies in K–12 Learning: A Meta-Analysis. Jacksonville, FL: College of Education and Human Services, University of Florida.

Cavanaugh, J. 2005. “Teaching Online: A Time Comparison.” Online Journal of Distance Learning and Administration 8, no. 1.

Fuller, D., R. Norby, K. Pearce and S. Strand. 2000. “Internet Teaching by Style: Profiling the Online Professor.” Educational Technology & Society 3, no. 2.

Greenberg, A. 2004. Navigating the Sea of Research on Video Conferencing-Based Distance Education: A Platform for Understanding Research into the Technology’s Effectiveness and Value. Wainhouse Research.

Hurd, M. 1999. “Anchoring and Acquiescence Bias in Measuring Assets in Household Surveys.” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 19, no. 1–3: 111–36.

Kearsley, G., and R. Blomeyer. 2004. “Preparing K–12 Teachers to Teach Online.” Educational Technology 44, Jan-Feb: 49–52.

McRae, P. 2011. “The Politics of Personalization in the 21st Century.” The ATA Magazine 91, no. 2.

McRae, P., S. Varnhagen, J.C. Couture and B. Arkison. 2009. “A Study of Alberta Teachers’ Working Condition in Distributed Learning Environments: Flexibility, Accessibility and Permeable Boundaries.” Proceedings of the American Education Research Association (AERA) Annual Conference, San Diego, CA: AERA.

Murphy, E., and M.A. Rodriguez-Manzanares. 2009. “Sage Without a Stage: Expanding the Object of Teaching in a Web-Based High School Classroom.” International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning 10, no. 3: 1–19.

Schifter, C. 2002. “Perception Differences About Participating in Distance Education.” Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration 1.

Sellani, R. J., and W. Harrington. 2002. “Addressing Administrator/Faculty Conflict in an Academic Online Environment.” Internet and Higher Education 5: 131–45.

Spector, J. 2005. “Time Demands in Online Instruction.” Distance Learning 26, no. 1.

Stanford, P., M.W. Crowe and H. Flice. 2010. “Differentiating with Technology.” TEACHING Exceptional Children Plus 6, no. 4. Available from http://escholarship.bc.edu/ education/tecplus/vol6/iss4/art2 (accessed March 24, 2010).

Thompson, M. 2004. “Engagement or ‘Encagement’? Faculty Workload in the Online Environment.” Paper presented at the 20th Annual Conference on Distance Teaching and Learning. Available at http://escholarship.bc.edu/ education/ tecplus/ vol6/iss4/art2Thompson.

Tomei, L. 2004. “The Impact of Online Teaching on Faculty Load.” The International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning 1, January. Available from www.itdl.org/journal/jan04/article04.htm .

________________________

Dr. Phil McRae is an executive staff officer with the Alberta Teachers’ Association and an adjunct professor with the Faculty of Education, University of Alberta.

Dr. Stanley Varnhagen and Bradley Arkison are members of the evaluative research team, Faculty of Extension, University of Alberta.